God's Stories #9: Elijah

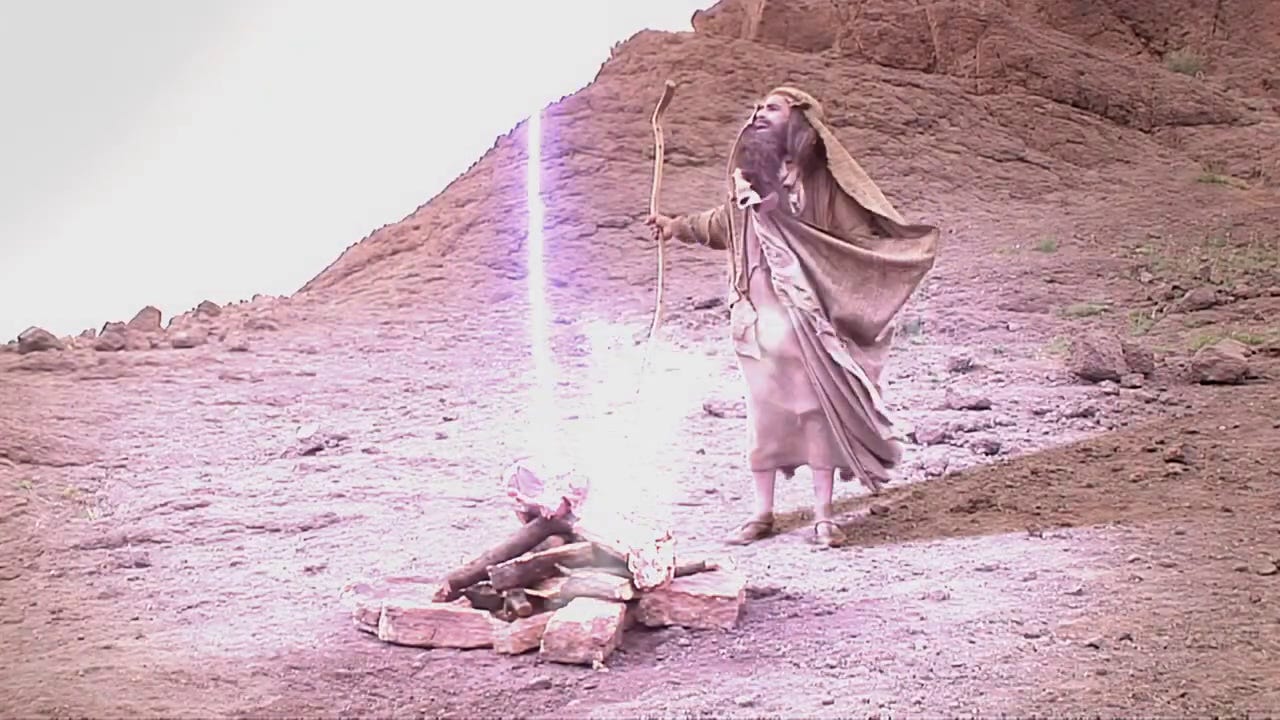

A rarely-filmed prophet gets the last word in this series of Arabic Bible movies.

Elijah is one of the more important figures in the Bible, but there have been very few films about him—certainly very few that lasted more than half an hour.1 So I was intrigued when I saw that the final film in ‘God’s Stories’, the nine-part Arabic movie series that I’ve been writing about this summer, was going to be all about him.

The first eight films in this series have sometimes come at their subjects from unusual angles, but the subjects themselves have all been fairly standard: five films are based on the book of Genesis, one is about Moses, and two are about Samuel and the kings he anointed. These are the same basic stories that tend to get prioritized in other tours through the Old Testament like ‘The Bible Collection’ or the 2013 miniseries The Bible.

But the story of Elijah, which takes place less than a century after Israel split into two rival kingdoms, is often omitted from this sort of series. If I had to speculate, I might say that that’s because Elijah’s story takes place in the northern kingdom of Israel, which ultimately faded from history, whereas those other series tend to focus on the southern kingdom of Judah, which eventually became the Roman province of Judea where Jesus was born. The southern kingdom fits easily into a trajectory that bridges the Old and New Testaments; the northern kingdom, maybe not so much.2

Whatever the reason, it’s interesting how ‘God’s Stories’ goes the opposite route, by skipping the southern kingdom altogether and focusing on Elijah—and in a way that also seems to bridge the Old and New Testaments. More on that below.

In the meantime, a few quick points:

This film is essentially about the relationship between Elijah and King Ahab, so it covers all of the stories that concern both men (I Kings 17-19, 21). It also has an opening sequence about Ahab’s marriage to Jezebel and his endorsement of the prophets of Baal (I Kings 16:29-33), and it has a closing sequence in which Elisha witnesses Elijah’s ascension into heaven (II Kings 2:1-13). The film does not depict any of Ahab’s dealings with the other prophets of God (I Kings 20, 22)—though it does allude to one of them in a quick bit of voice-over narration—nor does it depict Elijah’s confrontation with Ahab’s son Ahaziah (II Kings 1).

For the most part, the film sticks fairly close to the biblical text, but there is one major, major exception: It really plays up the notion that Ahab and Jezebel were not just idolaters but hedonists engaging in (off-screen) group sex with slave girls and priestesses—all in the name of encouraging the gods to be fertile, of course. (Well, at least some of it is done for that reason.) When Elijah announces that there will be no rain for the next few years, he goes beyond the text and tells Ahab and Jezebel that they have provoked God with their “filthiness”.

Ahab, of course, is just a guy looking to get laid, mainly, but Jezebel comes off as kinkier, more perverse; in one scene, the Baal worshippers dance in a circle and whip themselves, and Jezebel, sitting in their midst, really seems to enjoy the drops of blood that splatter onto her face. This ties into a longstanding pattern where “bad” women are assumed to be not just greedy or corrupt but sexually deviant, as well. Suffice it to say that there is nothing in the text to warrant this focus on Jezebel’s sexual appetites. Fertility rites, yes, a lot of ancient religions had that. Self-harm on the part of the prophets, yes, the text describes them doing that, too (I Kings 18:28).3 Jezebel getting off on all that stuff personally, and taking extra women into bed with her and her husband outside of the religious ceremonies, no, the text does not describe that.

A few other quick points about Ahab, Jezebel, and their set-up: The film does not depict any of their relatives—not the sons who succeeded Ahab on the throne, not the daughter who was married off to the king of Judah, and not the parents of Jezebel’s (her father was the king of Sidon) who married her off to Ahab. Instead, it seems Ahab’s chief priest introduces Ahab to Jezebel, and it seems Ahab and his court were worshiping Baal before Jezebel came along. The chief priest, for his part, dances like he’s in a mindless trance during the Baal-worshiping rituals. And Ahab, for his part, always seems to be drunk.

Fortunately, there is at least one positive female character in this film, though she doesn’t get anywhere near as much screen time as Jezebel does. During the drought, Elijah goes to Zarephath and stays with a widow and her son, and the film amplifies their relationship, so that when the boy dies and Elijah brings him back to life, it matters to us a little more than it might have otherwise. When Elijah has to leave them and go back to Israel, he thanks the woman for her devotion to him, and the boy sheds a tear as he hugs Elijah goodbye.

When Elijah first speaks to the widow, we don’t see him at all; instead, the camera looks at the widow, and we see Elijah’s shadow on the wall behind her. It’s a striking shot, reminiscent of the shadow that Jesus casts on a wall from somewhere offscreen during one of the healing scenes in Nicholas Ray’s King of Kings (1961). And, looking at my notes on Sins of Jezebel (1953)—the only Hollywood movie about Elijah that I know of—I see that there was at least one significant shot of Elijah’s shadow against the wall in that film, too.

Some of the extra dialogue between Elijah and the widow’s son is reminiscent of other scenes in this series that have focused on the relationship between father figures and younger men or boys. That sense of the faith being transmitted to new generations will continue, of course, in the scenes between Elijah and Elisha, though it’s clearer with the widow’s son. (Elisha sometimes feels to me more like someone that Elijah can deliver exposition to.)

When Elijah prays for the boy’s resuscitation, he leans across the boy’s body at a perpendicular angle, across the boy’s abdomen. That surprised me, because Elisha performs a very similar miracle in the Bible, and in that case, the text says he “lay on the boy, mouth to mouth, eyes to eyes, hands to hands” (II Kings 4:34), and I had always assumed that the two miracles were basically identical. But in Elijah’s case, the text doesn’t specify what position Elijah assumed when he “stretched himself out” on the boy (I Kings 17:21), so … okay.

Some of the most famous details in the stories about Elijah are surprisingly downplayed here, if not outright eliminated. Some of these omissions could be due to budget limitations—we don’t see Elijah racing Ahab’s chariot, for example—but others can’t be explained away so easily. Most notably, Elijah does not mock Baal or his prophets here the way he does in the text. He just gets some people to build his own altar while the prophets of Baal are busy tiring themselves out. (As someone who grew up in the Christian subculture with a love for the humour of Steve Taylor, The Wittenburg Door, and others, I always pointed to Elijah’s mockery of the prophets of Baal whenever my fellow Christians questioned the appropriateness of satire and the like.)

Curiously, when Elijah shouts that the people must seize the prophets of Baal and kill them all, we don’t actually see who Elijah is talking to. There is simply no crowd onscreen. What’s more, the prophets of Baal are all exhausted and lying unconscious on the ground—so it seems a bit odd that Elijah would make a point of saying that the prophets should be seized before they get away. The situation doesn’t seem quite as urgent as he makes it out to be.

Notably, the film does not show the Israelites killing the prophets of Baal, but it does show people stoning Naboth to death later on, and the camera lingers on Naboth’s blood because that’s what the text does (e.g. I Kings 21:19).

We also don’t get to see Ahab’s reaction when Elijah wins the contest. But we do see him tell Jezebel all about it after the fact. He mentions that the crowd was shouting “God is the Lord!”, and then he pauses to note that they were also shouting “Elijah!”, and he says “Elijah” means “God is the Lord.” Technically, I believe the more accurate translation for the Hebrew in this passage (“Yehovah hu Elohim”) would be “The Lord, he is God!” But yes, Elijah’s name is basically synonymous with what the crowds were shouting, and I have always wondered if the crowd’s shouts did sound like they were shouting Elijah’s name.

Budget limitations may have prevented this film from showing big crowds, racing chariots, or battle scenes—basically anything that would have required a lot of actual people and physical objects (costumes, props, etc.) in front of the camera—but the new visual effects are pretty good, especially when an earthquake cracks the ground open while Elijah is on Mt Horeb.

There is one other part of the biblical story that gets expanded, rather than reduced, in the telling here: namely, the bit where Ahab humbles himself after Elijah rebukes him for his role in the death of Naboth. Ahab’s humility gets a single verse in the text (I Kings 21:27), and it would have been very easy to squeeze Ahab’s self-humbling and God’s response to it into the very same scene where Elijah rebukes Ahab—but instead, the film lingers on Ahab’s guilt after Elijah rebukes him, and it presents Ahab’s self-humbling as something that drags on for days, such that God ends up sending Elijah back to amend his previous condemnation of Ahab. (This extended treatment of Ahab’s self-humbling is definitely warranted, I think, since the text says Ahab “put on sackcloth and fasted … and went around meekly”, which suggests a prolonged activity and not just a knee-jerk reaction to Elijah’s rebuke. But it’s such a short verse, and the film zips past so many other bits so quickly, that I think it’s significant how the film actually dwells on this part of Ahab’s story.)

As noted above, the film never gets into the fact that Ahab and Jezebel—depicted here as lustful hedonists—had a family with children who grew up and became kings and queens themselves. Elijah says that, when Ahab dies, Jezebel won’t be a queen any more … but surely she went on to be queen mother when her sons reigned? At any rate, the biblical Jezebel outlived Ahab by at least a dozen years. And their daughter Athaliah—who married the king of Judah and seized the throne after her own son’s death—outlived Jezebel by another seven years. So Ahab’s dynasty survived him, in one form or another, for about two decades. (Ahab’s dynasty arguably never ended, since all of the Judean kings after Athaliah were descendants of hers and thus of his, starting with her grandson Joash—but between geography and patrilineal descent, those kings are primarily identified as the heirs to King David’s dynasty.)

The final scene, in which Elijah ascends to heaven in a chariot of fire, is quite striking. It’s not what you necessarily expect visually—instead of flaming horses and an actual chariot with wheels or whatever, we see a sort of fiery sphere come down and envelop Elijah before carrying him away—but we do hear a bit of neighing in the sound effects as the sphere flies off. So it’s a bit horsey.

The film ends with the narrator reciting Malachi 4:5-6: “Behold, I will send you Elijah the prophet before the coming of the great and dreadful day of the Lord. And he shall turn the hearts of the fathers to their children and the hearts of the children to their fathers lest I come and smite the earth with a curse.” In some Christian Bibles, these are the last two verses of the Old Testament—so they lead right into the New Testament and its early description of John the Baptist, who was acclaimed by Jesus himself as a fulfillment of the prophecy that Elijah would return (Mark 9:11-13; Matthew 11:11-14, 17:10-13).

And that seems like a fitting note on which to end this Old Testament series, given that producer Robert Savo’s next biblical film was The Savior, a life-of-Jesus movie that I have written a little about in the past. Maybe I’ll say more about it, soon.

-

There is only one Hollywood feature film about Elijah that I know of, i.e. Sins of Jezebel (dir. Reginald Le Borg, 1953), and I wrote about it at my blog in 2013.

-

The ‘God’s Stories’ films can be purchased online at the GII Store. Note: It is possible that some of these titles might not be the upgraded versions of those films.

-

Bits of Elijah appear in this super-trailer for the ‘God’s Stories’ series:

Elijah also has its own trailer:

There have been a handful of animated and live-action short films about Elijah, but not that many. I am aware of only two feature films about him: 1953’s Sins of Jezebel and 2010’s Blast and Whisper. (The ‘God’s Stories’ film being reviewed here is 57 minutes, which may or may not make it a feature film depending on one’s definition.) I am also aware of two TV miniseries about Elijah, both from Brazil: 1997’s O Desafio de Elias and 2019’s Jezabel.

Compare this to how the book of II Chronicles, which is basically a rewrite of I & II Kings, focuses entirely on the southern kingdom and virtually ignores the northern kingdom—which means that there are virtually no stories about Elijah in that book, too. (Although, interestingly, II Chronicles 21:12-15 describes a letter that Elijah sent to the Judean king Jehoram, condemning him, which I & II Kings do not describe.)

Curiously, while the film shows the prophets of Baal engaging in self-harm as part of their routine religious practice, it does not show them doing this during the contest on Mt Carmel, which is the context in which the biblical text mentions it. The biblical text also says the prophets harmed themselves “with swords and spears”, not with whips.