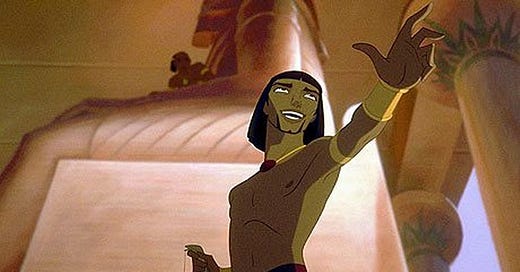

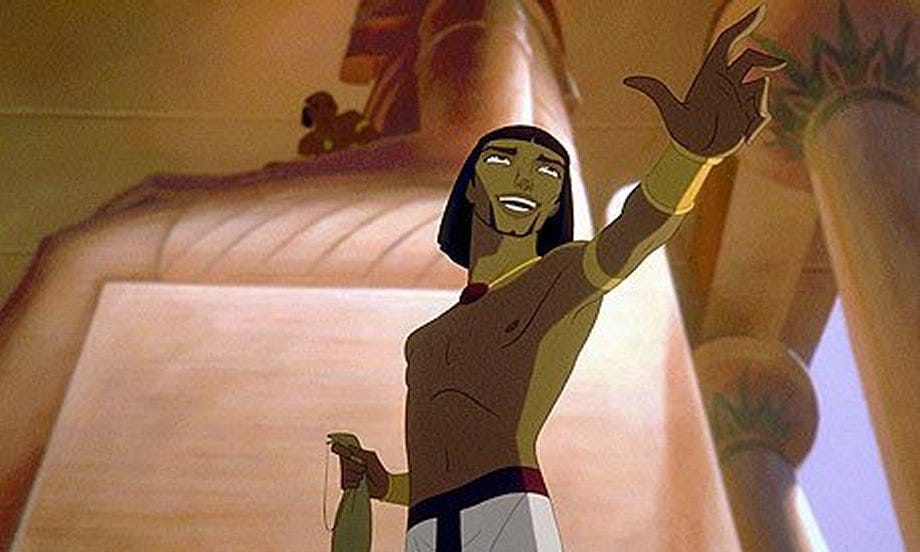

An Animated Moses: The Prince of Egypt

A detailed look at the making, and meaning, of the Bible film at the heart of one of the most revolutionary decades in the history of animation.

A few years ago I was talking to a publisher about possibly writing a book that would look at the history of film through the lens of Bible movies: each chapter would look at a particular film—roughly one per decade—and at how each film reflected the era in which it was made. I wrote a sample chapter to give some idea as to what the book would be like, and the film I focused on was 1998’s The Prince of Egypt, which I figured was old enough that we could have some sort of perspective on it now, but recent enough that I could make use of what I had learned about the film while covering it as a journalist. Also, this was the only chapter that was going to focus on animation, so it gave me an opportunity to cover pretty much the entire history of cinema—or at least this aspect of it—whereas the other chapters would have had a narrower scope, focusing on just a decade or two at a time. Alas, the book never came to be, but I didn’t want this chapter to go to waste, so I’m posting it here for paid subscribers on the weekend of the 24th anniversary of the film’s original theatrical release. Enjoy.

An Animated Moses: The Prince of Egypt

The last decades of the 20th century were a revolutionary time for the medium of animation. Animated films, once dismissed as little more than children’s entertainment, became increasingly popular among adults and even competed with live-action films for cultural prestige. The medium itself was transformed by the arrival of new technologies that broadened the range of images that animators could create. New companies emerged that challenged Disney’s decades-long dominance within the field. And one of the key films at the heart of all these changes was a Bible movie—The Prince of Egypt, a musical adaptation of the story of Moses—that was, by far, the most successful movie to be made within the biblical genre since its heyday in the 1950s and 1960s.

A brief history of animation

Filmmakers had been dabbling in animation from the medium’s earliest days. Indeed, in some ways animation pre-dates film: before there were forms of photography fast enough to capture reality at twenty-four frames a second, there were devices such as the fantascope (a spinning disc with sixteen images viewed in rapid succession through an aperture, introduced in 1833) and the flip book (patented in 1868) that created the illusion of movement with hand-drawn images. In 1888, a Frenchman named Charles-Émile Reynaud introduced perforated film strips to the world when he patented the Théâtre Optique system, which projected a series of animated hand-painted characters onto a screen while simultaneously projecting a static background onto the same screen. His Pantomimes Lumineuses premiered in Paris in 1892, three years before the Lumière brothers held the first public screening of their live-action “actuality” films.

It didn’t take long for filmmakers to combine the two kinds of moving image. Some of the earliest animated films were hybrid films that combined live-action with animation. In The Enchanted Drawing (1900), a man draws a face on a board, and the film uses jump cuts to show changes to the face’s expression as the man gives it a cigar and a drink; the man also draws objects, such as a hat and a bottle, that become “real” as needed. Other films were made that consisted of nothing but animation, through frame-by-frame manipulation of hand-drawn line art (e.g. Gertie the Dinosaur, 1914) and cardboard cutouts (e.g. The Adventures of Prince Achmed, 1926).

The introduction of synchronized sound in the late 1920s gave one American animator an opportunity to become the dominant figure in his field. Walt Disney—who had already overseen the hybrid Alice series (1923-1927), about a live-action girl who lives in an animated environment with her animated cat—released Steamboat Willie, the first cartoon to have a fully post-produced soundtrack, in 1928, and both he and the film’s protagonist, Mickey Mouse, became an overnight sensation. The financial success of Disney’s short films allowed him to pour all his resources into producing his first feature film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarves (1937), just nine years later—and the financial success of that film laid the groundwork for all the Disney features that followed, several of which, like Snow White, were based on fairy tales.

After Walt died of lung cancer in 1966, however, his company fell into something of a slump. While the studio named for him went on to have some success with films like Robin Hood (1973) and The Rescuers (1977), the new films didn’t have the artistic ambition or cultural cachet of its earlier hits. An animation director named Don Bluth left the company in 1979 and took almost a dozen of his fellow animators with him, claiming that Disney had lost its way; as independent filmmakers, Bluth and his colleagues went on to produce such acclaimed and popular films as The Secret of NIMH (1982), An American Tail (1986) and The Land Before Time (1988), the latter two of which were produced by Steven Spielberg, a highly successful filmmaker who was himself a huge fan of animation. The Disney studio, meanwhile, hit rock bottom when The Black Cauldron (1985), a particularly expensive project that had been in the works for over a decade, flopped. As Walt’s nephew and Disney board member Roy E. Disney put it, it particularly hurt that The Black Cauldron earned less money that year than The Care Bears Movie.1

By that point, however, things were beginning to turn around. In 1984, Disney brought in some new executives—including Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg, who had launched the Star Trek and Indiana Jones movie franchises at Paramount—to shake things up. While their primary focus was live-action films, including Disney’s first-ever R-rated movies, Katzenberg took the animation division under his wing and began pushing it in a more mature direction. The first clear sign of success was Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), a murder mystery that introduced some fairly grown-up animated characters—including a sexy femme fatale and a smoking, cussing baby—and put them in a live-action world. (This film, too, was co-produced by Spielberg, who played a key role in sweet-talking the other studios into letting their trademarked characters have cameos in Disney’s film.) Adults loved it, and it became one of the biggest hits of the year. This was followed by a string of animated films that were written like Broadway musicals, starting with The Little Mermaid (1989). Again, adults loved what they saw. Beauty and the Beast (1991) became the first animated movie to be nominated for the Oscar for Best Picture; Aladdin (1992) became the first to gross over $200 million in North America; The Lion King (1994) became the first to gross over $300 million.

The “Disney renaissance,” as it came to be called, inspired studios all over Hollywood to set up their own animation divisions, and top animators saw their salaries soar as the demand for their talents increased.2 The results, however, were mixed. 20th Century Fox hired Bluth to direct Anastasia (1997), which was a modest success, and Titan A.E. (2000), which wasn’t. Paramount played it safe with big-screen spin-offs of TV shows produced by its sister corporations, such as MTV’s Beavis & Butthead Do America (1996) and Nickelodeon’s The Rugrats Movie (1998). Warner Brothers had a hit with Space Jam (1996), a hybrid film that featured Bugs Bunny and basketball star Michael Jordan, but the studio’s fully-animated films were flops regardless of whether the reviews were bad (The Quest for Camelot, 1998) or good (The Iron Giant, 1999).

Meanwhile, as existing studios scrambled to hop aboard the animation bandwagon, the man who had overseen Disney’s renaissance decided to start a studio of his own.

The making of The Prince of Egypt

In 1994, just two and a half months before the release of The Lion King, Disney president Frank Wells died in a helicopter crash. Jeffrey Katzenberg, who had spent a decade turning the company’s movie studio into one of the most successful in Hollywood, believed the now-vacant presidency should go to him. Disney CEO Michael Eisner, on the other hand, disagreed, and told Katzenberg he was out of a job altogether.

Katzenberg quickly rebounded by teaming up with Steven Spielberg and music mogul David Geffen to announce the creation of a new company, DreamWorks SKG, that would produce and distribute its own movies, music, TV shows, and video games. At one of the very first meetings between the three co-founders, Katzenberg said he wanted to do things with animation that went beyond the fairy-tale formula perfected at Disney. Live-action films, he said, could be as different as Indiana Jones, Terminator 2 and Lawrence of Arabia, so why couldn’t animated films have that kind of diversity too? Spielberg, who had referenced the story of Moses in films like Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), leaned forward and replied, “Well, good, why don’t you do The Ten Commandments as our first movie?” Katzenberg immediately agreed, and so did Geffen, who cautioned, “But if you do it, you can’t tell a fairy tale. You’re going to have to go about telling this with a sense of respect and integrity that nobody’s done in modern times.”3 And so the movie that would set the new studio apart from Disney and all the others was set to be a biblical one.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thoughts and Spoilers to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.