Solomon and the Djinn: two movies

George Miller's Three Thousand Years of Longing and the Iranian film The Kingdom of Solomon both tap into non-biblical legends about King Solomon's power over spiritual beings.

There’s not a whole lot in the biblical story of Solomon that could be called supernatural. God spoke to Solomon in a couple of dreams (I Kings 3, 9; II Chronicles 1, 7), and God revealed himself at the Temple’s dedication ceremony, via a cloud that represented his glory (I Kings 8, II Chronicles 5) and a fire that consumed the Israelites’ sacrifices (II Chronicles 7). And that’s about it.

For the most part, the biblical record is all about Solomon’s wisdom, his building projects, the women in his life, and the violence it took to hold on to his throne—whether that violence was aimed at his own family or at people who started rebellions against him. And as far as I can tell, those sorts of distinctly non-supernatural subjects are what most films about Solomon have focused on, too.

But the later apocryphal texts went further than that, and imagined that Solomon was not merely a witness to God’s mighty deeds but an actively supernatural figure himself—one who had authority over demons, even. This theme was picked up in Islam, where Solomon is regarded as a prophet who had control over the wind, the demons, and the djinn (genies), and he could speak the languages of animals as well.

There is a film in theatres right now that touches—very briefly—on the legends about Solomon and his control over spirits and animals, and it prompted me to finally take a look at an Iranian movie about Solomon that, coming from a Muslim perspective, delves even deeper into the legends about Solomon’s supernatural exploits.

Here are some quick points about each film:

Three Thousand Years of Longing (dir. George Miller, 2022)

This film, which stars Idris Elba as a Djinn who has been trapped in bottles three times over the past three millennia, is based on A.S. Byatt’s 1994 novella The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye. The protagonist is a narratologist named Alithea Binnie (played in the film by Tilda Swinton) who buys a bottle in Istanbul, takes it back to her hotel room, and unleashes the Djinn within. The Djinn asks her to make three wishes, but she persuades him to tell her the story of the events that led to his previous entrapments.

In the novella, Alithea (whose name in the book is actually Gillian Perholt) doesn’t buy the bottle until halfway through the story, but in the film it’s practically the first thing she does. In the novella, Alithea spends the first half of the story touring Turkey with colleagues and talking about stories—about the Canterbury Tales, the Epic of Gilgamesh, the New Testament, and so on—and echoes of these stories are felt later on in the novella’s resolution. But the film cuts all of these things out, which makes the Djinn much, much more central to the movie than he is to the book—and, as Bonnie Johnson notes in a great book-to-film comparison in the Los Angeles Times, it also has the effect of reducing Alithea “to the familiar figure of asocial intellectual.”

The film also changes the ending, in a way that suggests it doesn’t really know what the story’s supposed to be about. It adds a gratuitous dig at Alithea’s xenophobic neighbours back in the UK, which has nothing to do with Byatt’s story, and it starts to go in an almost sci-fi direction when … I shall try to be vague … it introduces the subject of electromagnetic waves.

Not surprisingly, George Miller—the director of such visually wild and inventive films as Mad Max: Fury Road—is primarily interested in the Djinn’s three stories and the opportunity they give him to create some spectacular visuals, all set in a sort of fairy-tale past. And this is where Solomon comes in.

Like a lot of films, this one imagines that there was a relationship between Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. Unlike those other films, this one imagines that Solomon came to the Queen’s court, not vice versa. It also imagines that she was part-djinn, and related on some level to the Djinn played by Idris Elba. (We are informed that humans and djinn can have offspring together, but the offspring cannot have children of their own—similar to how horses and donkeys can produce infertile mules. So if the Queen of Sheba is, herself, a hybrid in this story, then presumably all the legends about her and Solomon having a child together don’t take place in this universe.)

Interestingly, Solomon seduces the Queen of Sheba partly through his musical skills, which are clearly fantastical in their own way: while he plucks some of the strings himself, the chair-sized instrument he plays and sits in has hands, feet, and a mouth that add their own elements to his music. (I was reminded of the old Disney cartoon Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom!) While the biblical Solomon is credited with authoring the Song of Songs, the playing of musical instruments is generally held to be his father David’s domain.

The Queen of Sheba gives Solomon a few tests to pass before she gives in to him, and he passes these tests with help from some ants and a demon known as an ifrit, both of whom Solomon can either speak to or control.

The Djinn is jealous of Solomon—he wanted the Queen of Sheba for himself—so Solomon, while having sex with the Queen, traps the Djinn in a bottle and tosses it into the Red Sea. And that’s the end of the first story.

For what it’s worth, the Djinn’s second story begins two and a half thousand years later, during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent in the 16th century, and extends to the reign of Suleiman’s great-great-great-grandson Ibrahim the Mad in the 17th century; the latter is the guy whose harem is full of fur-covered walls and overweight concubines. This is followed by the third story, which takes place in the 19th century and concerns a woman whose scientific pursuits are held back by the fact that her husband keeps her locked in the house. And then there’s the story that takes place “today”, when the Djinn meets the narratologist.

If you’re wondering what to expect from the film content-wise, in the United States it’s rated R for “some sexual content, graphic nudity and brief violence”, and where I live—in British Columbia, Canada—it’s rated PG for “violence, nudity, coarse language, sexually suggestive scenes”. So it’s one of those occasional films that gets an R in one country and a PG in the other, and not the PG-13 or 14-A rating that comes between those two ratings.

Incidentally, Nicolas Mouawad, the Lebanese actor who plays Solomon, is also reportedly playing Abraham in His Only Son, an American film that is currently in post-production, and he is going to play Jesus in Jesus and the Others, an international film that is currently in pre-production.

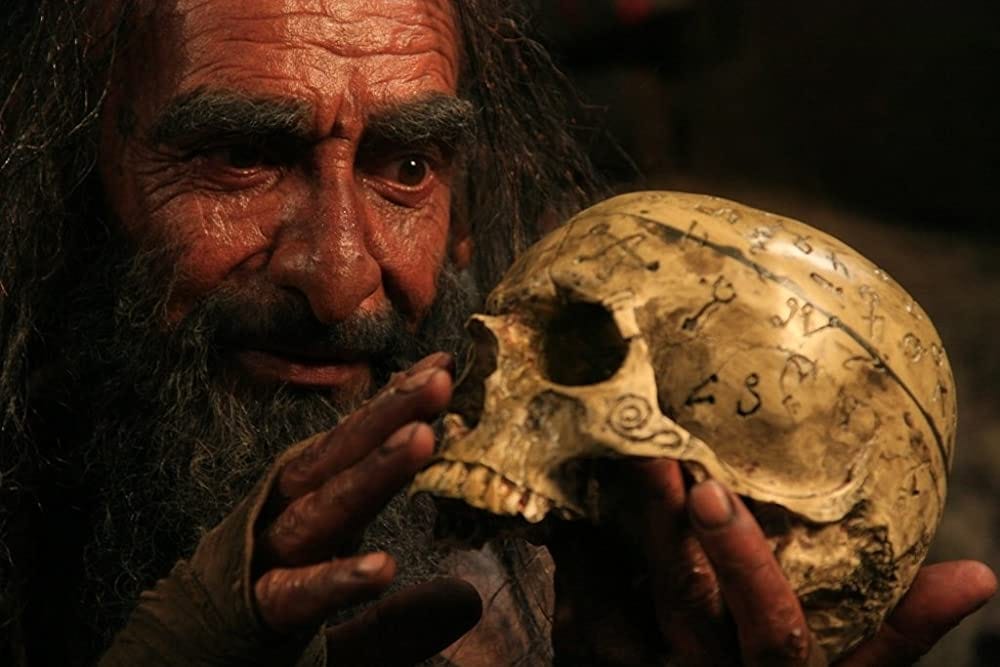

The Kingdom of Solomon (dir. Shahriar Bahrani, 2010)

This is actually Bahrani’s second film about a character who is featured in both the Christian and Muslim scriptures, following 2000’s Saint Mary.

Like other Muslim films based on characters from the Bible—such as the TV series Prophet Joseph or the film Jesus, the Spirit of God—this film makes a point of distancing its protagonist from Judaism in ways that get rather anti-Semitic at times. The Jewish leaders in this film don’t believe in demons or miracles, but they do collaborate with a sorcerer who says his magic comes from the Egyptians of Moses’ day and was secretly preserved all these years by the rabbis. The Jewish leaders insist it is they, and not the kings, who are the true guardians of Judaism, and they keep interest rates high to keep the people in debt. Solomon accuses them of editing the Torah to justify their actions, and God himself says many of the people are really following Satan. Ultimately, in the climactic battle, the Jewish leaders seem determined to slaughter the inhabitants of Jerusalem, even the women and children—and they are not above waving their Torah scrolls to make people lower their defenses.

The djinn and the devils are a threat throughout this movie, which actually starts with a sorcerer trying to summon them. We are told that djinn and devils merely tempted people in the past, but now they’re going to be more direct, by possessing people’s bodies or assuming some other material form. One shadowy spirit flies straight into Solomon’s pregnant wife and kills both her and her unborn child.

Solomon will ride into a crowd of possessed Israelites and kill them if he must—if, for example, they are violently attacking an entire community, including its women and children—but once the demoniacs have been captured, he makes a point of trying to redeem them, telling them to call on God even when they believe they are hopelessly “unclean”. In a word, the possessed have souls that can be saved. But God tells Solomon in a vision that Israel as a whole is like a corpse without a soul, and at one point Solomon dismisses the usurious legalists from his presence—the ones who say they have the Torah on their side—because he does not see any good in them. By the end of the film, as Solomon prepares to face the Jewish leaders who are threatening the inhabitants of Jerusalem, either he or one of his generals says, “This time we are facing the devils in human form,” and it is not at all clear that they are referring to mere possession any more. The leaders might be just that irredeemable.

There is a clear apocalyptic edge to all of this, as we are told that the evil spirits will eventually return at the end of time. However, Solomon points to a holy rock in Jerusalem—the very same rock that Muhammad will ascend from some day—and he says that, one day, Satan himself will be beheaded on this rock, and “then the heavenly kingdom of God will shine upon the earth.”

In real life, the holy rock in question—which now sits under the Dome of the Rock, a Muslim shrine that was first built in the 7th century—is believed to be where the Holy of Holies once stood in the Temple that Solomon built. There is no Temple in this film, but there is a sort of open-air canopy over the rock, which marks the rock as special but also keeps it nicely accessible.

This film follows the Muslim tradition in seriously cleaning up Solomon’s image. I don’t know how much of the clean-up is unique to the film and how much goes back to earlier traditions, but: He does not commit idolatry, he gets along great with all of his brothers and cousins (including Adonijah, Joab, and Absalom, all of whom either killed each other or were killed by Solomon in the Bible!), he appears to have only one wife (which is interesting, as the Muslim tradition does allow some polygamy, albeit not the thousand wives and concubines that the biblical Solomon had), he gets along great with kids, and he happily works in the field during the harvest season, just like everyone else (so, there are no complaints about him exploiting the people to maintain his wealthy lifestyle here like there are in the Bible…).

David is dead long before the film begins, but it seems the film might be cleaning up his image as well. Solomon’s mother in this film is Michal—who, in the Bible, was David’s estranged first wife and never had any children at all. The biblical Solomon’s mother, of course, was Bathsheba, whose affair with David was condemned by God through the prophet Nathan.

Stylistically, the film reminded me of The Lord of the Rings in a few places, especially when Solomon is riding his horse back to Jerusalem and he sees a vision of his wife, who has just died. (I found myself thinking of Arwen’s vision of Aragorn and their child.) The music over the fight scenes (full of strings and sad choruses), and the scenes of villages being burned by marauders, also brought that fantasy trilogy to mind. On the other hand, the film also got me thinking of, I dunno, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen or something similarly Gilliam-esque, when Solomon straps a few boats together and summons the winds to make his boats fly through the air to Jerusalem.

I don’t believe this film shows Solomon communicating with the animals per se, but early on, he tells some children about how the birds used to sing with his father David, and one child asks if Solomon can talk to birds too, and Solomon just smiles and holds out his hand so that a passing bird can land on it—and then he hands the bird to the children and they are amused by it.

And that about covers it, I think. More Solomon movies later, maybe.

-

I reviewed The Bible Collection: Solomon (dir. Roger Young, 1997) for BC Christian News in 2001, and I live-tweeted Solomon and Sheba (dir. King Vidor, 1959) in 2017.

-

Three Thousand Years of Longing is currently playing in theatres. The images from that film above are taken from this trailer:

The version of The Kingdom of Solomon that I watched was this one on YouTube: