Flashback: When We Were Kings (1996)

My interview with Leon Gast, director of the Oscar-winning documentary about the legendary Rumble in the Jungle between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman.

There’s a new movie about boxing legend George Foreman in theatres this weekend—called, appropriately enough, Big George Foreman.

I’m not a sports person in the slightest, so I’m not planning to review the film.

However, the film does depict the ‘Rumble in the Jungle’, the 1974 boxing match in which Foreman lost his heavyweight championship title to Muhammad Ali—and some years ago, I had the good fortune to interview filmmaker Leon Gast about an Oscar-winning documentary he made about that fight, called When We Were Kings (1996).

The documentary, as I recall, is much more about Ali than Foreman—which makes sense, given that Ali was a very charismatic guy who actively sought the attention of the cameras, plus he did win the fight after all—but the film is at least partly about Foreman, so I figured I’d dig my interview out of the archives and share it here.

This article was first published in The Ubyssey on March 26, 1997. The film can now be streamed, with a couple of bonus features, on the Criterion Channel.

The Leon King

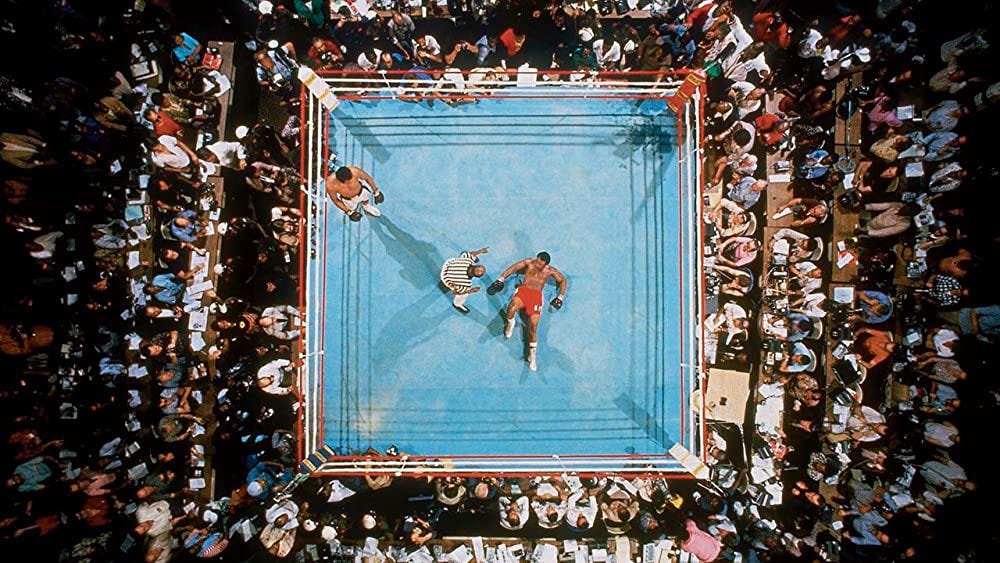

When Muhammad Ali met George Foreman in Zaire back in 1974, it wasn’t to shake his hand. Leon Gast captured their bout on film and, after a 21-year delay, got an Oscar for his patience.

It’s a story so good, they couldn’t have made it up. Muhammad Ali, stripped of his heavyweight championship in 1967 when he refused to fight in Vietnam, had a chance to win it back from current champ George Foreman when Don King masterminded the Rumble in the Jungle in Zaire in 1974.

The hard-hitting Foreman had recently knocked out Ken Norton and Joe Frazier, the only two men who had ever beaten Ali. And it was generally agreed that Ali, past his prime at 32, would be no match for the 26-year-old Foreman.

Instead, Ali withstood 15 rounds before sending Foreman to the mat. It was, and still remains, the only time Foreman has been knocked out. But for Ali, the match, set in the continent of his ancestors, was more than a fight. It was a vindication of his position, as a role model at a time when black pride was taking off.

Fortunately, Leon Gast was there with a camera crew to capture the moment. Don King had originally hired him to document the music festival that was supposed to play just before the fight. James Brown, B.B. King, Miriam Makeba and others all shared billing on what was dubbed, by some, “the Black Woodstock”—but a severe cut to Foreman’s face four days before the fight forced the pugilists to wait an extra six weeks before getting in the ring.

Even with this great story, Gast didn’t have enough money to finish the film. With his negatives held hostage in a film lab—ironically, this probably preserved the film better than any of Gast’s own efforts could have done—Gast spent the next 21 years living with “boxes and boxes and boxes” of material in his apartment, including 300,000 feet of film, 200,000 feet of corresponding sound and 32 hours of multi-track concert tape.

Salvation came in the form of David Sonenberg, a lawyer turned showbiz manager who financed the completion of the film over the last few years.

It’s been said Ali wouldn’t have won if it weren’t for the six-week stay in Zaire. The crowds in Zaire hated Foreman, who hid in the hotel, while they cheered Ali on with cries of “Ali, bomaye!” (“Ali, kill him!”)

Between the attention of the masses and the attention of the film crew, Ali used those six weeks to psych himself up. “Angelo Dundee, his trainer, would come in,” Gast recalls, “and he’d say, ‘Come on, champ, you’ve got to get back to the gym. You have to train.’ And Ali would say, ‘This is a different kind of training. This is just as important as the other stuff.’ And he would just keep on speaking to us.”

Ali had such a clear vision for the film, Gast began looking for opportunities to catch him off-guard, but Ali played with the camera every chance he got. “It’s like that persona on camera was the same as off-camera. He had that way of making you feel there was an honesty and a purity about him.”

Ali’s knack for off-the-cuff rhymes—“You think the world was surprised when Nixon resigned? / Just wait ’til I kick George Foreman’s behind” is a classic example—actually led him to record an album of his own, I Am the Greatest, back when he still went by the name Cassius Clay. For the new film, Ali teamed up with the Fugees to record ‘Rumble in the Jungle’.

With all the music on display, did Gast ever consider using any of Ali’s other recordings? “Yeah, I’ve got ’em!” Gast laughs. “Not only stuff that he did, but there were a couple of songs about him.” Gast begins to sing: “Muhammad Ali / Flew like a butterfly, stung like a bee.”

Gast laughs again. “Twenty-three years I’ve played around with this thing. I’ve played around with just about every possibility you can think of. I had his ‘Stand by Me’ in there at one time. We considered it but in the end, we didn’t use it.”

Gast originally wanted to forego narration and let the athletes and musicians speak for themselves, but co-editor Taylor Hackford, best known for directing An Officer and a Gentleman, pushed for talking heads, including Ali biographer Tom Hauser and journalists George Plimpton and Norman Mailer. They also turned to Spike Lee and Malik Bowens for commentary on how the fight affected black people on both sides of the Atlantic.

However, neither Ali nor Foreman makes a modern-day appearance. Gast almost invited them into the studio to bring his film up to date, but in the end, he kept his focus on 1974. “When I saw the [1996] Olympics, and that moment when Ali lit the torch, I thought, ‘Oh my God, what an image that is.’ And we cut it in so that the last image that you saw was the picture of Ali with the torch, and it was there for a couple of days. We had contacted George Foreman’s lawyer and manager, but then we realized, ‘No. It’s not necessary. To have that image of Ali is completely unnecessary; if anything, it’s a cheap shot.’ So we removed it, and we never continued with the negotiations with George. We figured, ‘Let it be about this event.’”

Gast also passed on the opportunity to bring audiences up to date on one other key player: event sponsor General Mobutu Sese Seko, whose 32-year grip on Zaire has slipped dramatically in recent months. “There are people who’ve said, ‘Why didn’t you let us know more about Zaire and what a despot Mobutu is and how he’s been running his country into the ground?’ But this is about the event, and I think you get a sense of what we feel about Mobutu in the film, a sense of the kind of dictator he was.”

Academics will probably debate the role Gast’s film crew played in motivating Ali’s victory for some time. But if Gast helped Ali win, Ali repaid the favour by helping to propel Gast’s film into this year’s Oscar race, where it was nominated for the Best Documentary award.

Speaking to The Ubyssey just three days before the ceremony, Gast notes that the documentary branch of the Academy typically resents—and will not nominate—non-fiction films with a semblance of popular appeal. “It meant so much to be nominated, since a lot of my favorite films—documentaries such as Hoop Dreams, Roger & Me, The Thin Blue Line, Brothers Keeper—were not nominated for the award when it was their turn. Just to be nominated is a huge victory, especially in this category, so we’re winners already.”

As it happens, Gast and his film did get the Oscar last Monday night. “It’s all due to Muhammad Ali, the hero of our times,” says Gast. “As the centrepiece of our film, he gave us a tremendous edge, so all the praise goes to him.”

A few extra notes about this article and its context:

It occurs to me now that this article makes no mention at all of the fact that Foreman won his title back in November 1994, becoming the oldest heavyweight champion ever at the age of 45. That was just two years and four months before I wrote this article. Take that omission as a sign of how out-of-the-loop I am when it comes to sports.

The article does mention how Mobutu’s “grip on Zaire” had slipped in recent months. In the end, Mobutu died and the country changed its name back to Congo—specifically the Democratic Republic of the Congo—within months of this article’s publication.

I was the Culture Editor at the UBC student newspaper back then, and the Oscars that year happened to take place on one of our production nights. I had interviewed Gast just a few days earlier, and my article was going to be laid out that night, so I asked him for a quote that I could slip in at the last minute if his movie won—which it did.

Until today, I had never actually seen Gast accept his Oscar, because I was at the student newspaper office that night. (I was busy doing the layout for my entire section, and someone else was keeping tabs on the ceremony.) So here is that acceptance speech:

Note: Ali and Foreman were both in the audience that night, and Gast thanks Foreman “for being who he was back then and who he is now.” Also: the award was presented by Tommy Lee Jones and Will Smith, just two months before Men in Black came out. Smith went on to be Oscar-nominated for playing Ali—in, natch, Ali—just five years later.

And, for fun, here’s the trailer for When We Were Kings, followed by clips from the Ali and Foreman biopics that have now dramatized the ‘Rumble in the Jungle’: