Flashback: The Exorcist (1973)

The movie is half a century old this year, and it's getting a new sequel this week. Here's what I've written about the original movie in the past.

There’s a new sequel to The Exorcist coming out this week, so I figured I’d take a look back at some of the things I’ve written about that film and its various sequels, prequels, and spin-offs over the years—linking to comments of mine that are still online, and re-posting those that aren’t.

Today, I’m focusing on the original film, which came out almost 50 years ago, on the day after Christmas in 1973.

I was a little young to see The Exorcist when it first came out, but I caught up with it as an adult, and when it was re-released with extra footage in September 2000, I wrote an article about the film for BC Christian News, as well as a review of the expanded version of the film for the Vancouver Courier.

A few years later, I made a point of reading the original novel and watching the first two sequels—1977’s Exorcist II: The Heretic and 1990’s The Exorcist III—while preparing to write a review of the fourth film, 2004’s Exorcist: The Beginning.

Along the way, I wrote some long-ish comments about the novel and the films at the Arts & Faith discussion board, which was one of my favorite hangouts in the days before social media. That discussion board no longer exists, alas, so instead of linking to those comments, I figured I’d re-post them here at Substack.

First, on July 21, 2004, I wrote this:

Just wondering, has anyone here read William Peter Blatty’s original novel? I’m just about finished reading it, and I have to say, it makes for an interesting read—the film follows the book very, very closely (with just a couple of minor characters and/or subplots trimmed for expediency’s sake), but, if anything, the theological elements, and that tension between ancient faith and scientific doubt, actually come through more strongly in the book than they do in the film.

I also find myself wondering how the change in medium (um, no pun intended) might affect the way the story works on its audience. The book is constantly depicting things from the points of view of certain characters—we are constantly inside the heads of anxious mother Chris MacNeil, doubting Jesuit Damien Karras, and disarmingly casual police officer Lt. Kinderman—but we never get inside the head of Regan or the demon that possesses her, so we are encouraged to identify with the other characters much, much more than we might identify with the demon. And yet the film cannot take us inside these inner monologues quite so easily—so when characters sit down with the possessed girl, we view them more or less equally, and the demon kind of overwhelms the scene through the sheer force of its shocking spectacle. At least, that’s a theory I’m toying with right now.

More later. In the meantime, it never ceases to intrigue me how popular this film was in its day—it remains the 9th-highest-grossing film of all time, once figures are adjusted for inflation, and it is quite possible that, at the time of its release in 1973, it was the top-grossing film of all time in raw dollars; it’s difficult to say, since the website I link to there includes later re-issues among the grosses, and the only other films in that league at that time were Gone with the Wind and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and all three films have been given fairly wide re-issues at least once since then.

Then, on August 6, 2004, I wrote:

Oh, man. Oy vey. Today I finally went ahead and did my Exorcist marathon; thankfully, a friend of mine who happens to be a big fan of the first film joined me for the second and third films, so I wasn’t entirely alone in my suffering.

I took a few notes and I’ll get around to posting them in a day or two, when I have time. But I just wanted to get out of my system the fact that I had seen all three films in a row. I still like the original film, a lot. The second one is very, very bad, but so bad that it attains a kind of risible charm—no, not charm, but at least it gives you a reason to laugh. The third film is better, but in a way that doesn’t really invite or allow you to mock it, so it’s actually less fun to watch.

I can only imagine what the prequel(s) will be like.

I can’t recall the last time I did a marathon like this. Well, okay, I saw all three Lord of the Rings films on the big screen last December, but that event was not planned by me. It is self-planned home-video marathons that I cannot remember doing for some time.

And then, on August 17, 2004, I wrote:

Oh dear, oh dear, almost two weeks have gone by and I still haven’t posted my thoughts on the Exorcist sequels. I guess that will have to wait, still, since I first want to post a few comments on the original film and the novel that inspired it.

First, as some of you may know, The Exorcist was reportedly inspired by a real-life exorcism that took place back in the ’40s. You may be interested to know, then, that an investigative reporter tracked down the person who was possessed a few years ago, and came to the conclusion that what really happened was a whole lot less sensational than the story Blatty tells. In addition, my understanding is that Blatty’s novel and film do what a lot of fictional works do, in the sense that it takes pretty much every phenomenon known to be associated with demonic possession and piles ’em all into a single case, when in actual fact no more than a few of these phenomena ever appear at the same time. (It’s what I call the “Memphis Belle effect”—I don’t doubt that every single thing that happens to the WW2 bomber depicted in that film has some sort of historical precedent, but I highly doubt that ALL those things happened on any single bombing run.)

Having said all that, I have to say I don’t have a lot to say on the original film that I didn’t already say four years ago when the extended edition came out in theatres. I took very few notes when I saw that film two weeks ago; FWIW, I did note that the prologue at the archaeological site is said to have taken place in “Northern Iraq ... near Nineveh,” and I also noted that Father Merrin’s (Max von Sydow) earlier experience with exorcism, and with the demon Pazuzu (who is named in the novel and in the 1977 sequel but not in the original film itself), is said to have taken place “ten, twelve years ago in Africa” and is said to have lasted “months”. I am not entirely clear what connection this Assyrian demon or deity is supposed to have to African tribal religion, or why Merrin would know, upon digging up a small statue of this demon, that the demon would strike again in America, but anyhoo.

The two things that made the biggest impression on me, upon reading the novel, were the pronounced emphasis on death and nihilism, and the extreme lengths to which Father Karras (Jason Miller)—and, by extension, the Catholic Church—would go to try to explain away Regan’s symptoms in scientific terms, as anything but demonic possession. Both of these things are rather downplayed in the film.

First, the nihilism. Thomas Hibbs’s Shows About Nothing: Nihilism in Popular Culture from The Exorcist to Seinfeld makes some fascinating points about this film (and Hibbs, in his review of Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, makes the same point I did about Gibson’s film following in the footsteps of The Exorcist as it speaks boldly about the inescapable meaning of EVIL to a culture that has lost the ability to speak of ANY kind of meaning). But the sort of nihilism I see in the film is one in which the world is reduced to loud, noisy, mechanistic terms; the machines that pound-pound-clank as they probe Regan’s body, and the sounds of jet planes drowning out intimate conversation, all point to a world in which there is no room for Spirit because there is nothing more than Matter. The sort of nihilism addressed in the book, however, is of a somewhat different quality; in the book, we learn that Chris MacNeil (Ellen Burstyn) had a son who died at the age of three (before Regan was born, I think), and Chris is haunted by the “terrible clarity” of “irreversible” “non-being” (p. 15). Later Regan asks her mother why people die (pp. 42-43), and when Chris’s film director dies, she thinks again of “death and the worm and the void and unspeakable loneliness and stillness, darkness, underneath the sod, with nothing moving, no, no motion...” (p. 130). So there’s a definite hope for a reality, and a continuation of personhood, beyond this life that is answered somewhat ironically when the demon comes.

Second, the scientific terms. In the novel, Father Karras puts up a MUCH stronger effort to explain away Regan’s symptoms as anything OTHER than demonic possession, even going so far as to suppose that Regan’s speaking of Latin might be the result of some sort of telepathic reading of Karras’s mind, and even going so far as to suppose that psychokinesis of the sort displayed by Regan may also be explainable in purely scientific terms. It’s commendable to see that the Catholic church has, for centuries, gone out of its way not to be hoodwinked by every alleged case of possession that comes its way, but in an age where so MANY things seem explicable or quantifiable in scientific terms, you do begin to wonder how, exactly, the Catholic church can ever take that step of faith and declare that THIS particular item or THAT particular item is a sign of the spiritual world intruding on the physical world, instead of just one more item for which the scientists have various theories. (FWIW, Karras even suggests that the possession may just be schizophrenia, and that schizophrenia may be simply the result of the fact that consciousness arises from brain cells and different clusters of brain cells have different tasks and sometimes the dominant cluster gives way to one of the ordinarily subordinate clusters (p. 213)—and one does begin to wonder where the theological notion of “personhood” may fit in here.)

The book has some other interesting elements, too, that were left out of the film or differed with the film in some small way.

First, it’s made explicit that Regan herself is the one who desecrated the Catholic churches in the Georgetown area—it was never entirely clear to me, based on the film alone, whether it was she who had done this or whether there was some never-seen coven which might have been motivated by the demon’s arrival in that neighbourhood, and part of my confusion on this point was owed to the fact that the demon’s activity seems virtually confined to her bedroom (the major exception to this being the scene where Regan is hypnotized by the psychiatrist and the demon possesses her and grabs him by the testicles—but if the psychiatrist hadn’t done anything, the demon might not have appeared). But the book gives us a close-enough look at Lt. Kinderman’s investigation into Dennings’ death, so that we know what he knows, which is that all the evidence points to Regan being the one who desecrated the churches, perhaps while “sleepwalking”.

Second, there is a Catholic “seeress” who attends Chris’s party early in the story and gets odd vibes around Regan (pp. 59, 62-63, 68, 71, 74-77, 170). Here’s how she explains it: “‘I don’t know what you think of me,’ she said, speaking slowly. ‘Many people associate me with spiritualism. But that’s wrong. Yes, I think I have a gift,’ she continued quietly. ‘But it isn’t occult. In fact, to me it seems natural; perfectly natural. Being a Catholic, I believe that we all have a foot in two worlds. The one that we’re conscious of is time. But now and then a freak like me gets a flash from the other foot; and that one, I think ... is in eternity. Well, eternity has no time. There the future is present. So now and again when I feel that other foot, I believe that I get to see the future. Who knows? Maybe not. Maybe all of it’s coincidence.’ She shrugged. ‘But I think I do. And if that’s so, why, I still say it’s natural, you see. But now the occult...’ She paused, picking words. ‘The occult is something different. I’ve stayed away from that. I think dabbling with that can be dangerous. And that includes fooling around with a Ouija board.’ . . . It could all be suggestion. But in story after story that I’ve heard about séances, Ouija boards, all of that, they always seem to point to the opening of a door of some sort. Oh, not to the spirit world, perhaps; you don’t believe in that. Perhaps, then, a door in what you call the subconscious. I don’t know. All I know is that things seem to happen. And, my dear, there are lunatic asylums all over the world filled with people who dabbled in the occult.’” So, it seems she makes a difference between the “natural” “gift” that enables her to see into the future, on the one hand, and the more selfish attempt to make contact with spirits and manipulate them, which always seems to backfire.

Third, in the film, Father Karras PUNCHES the demon-possessed Regan when he discovers that Father Merrin is dead. But that is not how the book describes the incident, where Karras directs all his rage at the demon but none at the body of the girl (pp. 328-329): “Karras stared numbly at the spittle [which the demon has just spat onto Merrin’s eye], eyes bulging. Did not move. Could not hear above the roaring of his blood. And then slowly, in quivering, side-angling jerks, he looked up with a face that was a purpling snarl, an electrifying spasm of hatred and rage. ‘You son of a bitch!’ Karras seethed in a whisper that hissed into air like molten steel. ‘You bastard!’ Though he did not move, he seemed to be uncoiling, the sinews of his neck pulling taut like cables. The demon stopped laughing and eyed him with malevolence. ‘You were losing! You’ve always been a loser!’ Regan splattered him with vomit. He ignored it. ‘Yes, you’re very good with children!’ he said, trembling. ‘Little girls! Well, come on! Let’s see you try something bigger! Come on!’ He had his hands out like great, fleshy hooks, beckoning slowly. ‘Come on! Come on, loser! Try me! Leave the girl and take me! Take me! Come into...’ It was barely a minute later when Chris and Sharon heard the sounds from above. . . . both the women glanced up at the ceiling. Stumblings. Sharp bumps against furniture. Walls. Then the voice of ... the demon? The demon. Obscenities. But another voice. Alternating. Karras? Yes, Karras. Yet stronger. Deeper. ‘No! I won’t let you hurt them! You're not going to hurt them! You’re coming with...’ Chris knocked her drink over as she flinched at a violent splintering, at the breaking of glass . . . ”

Fourth, there is a little more detail about the teachings of Father Merrin, whose books “had stirred ferment in the Church, for they interpreted his faith in the terms of science, in terms of a matter that was still evolving, destined to be spirit and joined to God” (p. 287). However, when we are first introduced to him on his archaeological dig, the book describes his reaction to the bones of men thusly (p. 3): “The brittle remnants of cosmic torment that once made him wonder if matter was Lucifer upward-groping back to his God. And yet now he knew better.”

Oh, plus, the book begins with a page that includes a reference to the story in Luke about the demons being sent into the pigs, an FBI wiretap in which two Cosa Nostra guys discuss a guy they tortured, an account of some cruelties committed by the Communists, and the names “Dachau ... Auschwitz ... Buchenwald”. Section II (The Edge) begins with this quote from Aeschylus (p. 82): “...In our sleep, pain, which cannot forget, falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God...” Section III (The Abyss) begins with this series of quotes (p. 194): “They said, ‘What sign can you give us to see, so that we may believe you?’ John 6: 30-31 / ...A [Vietnam] brigade commander once ran a contest to rack up his unit’s 10,000th kill; the prize was a week of luxury in the colonel’s own quarters... Newsweek, 1969 / You do not believe although you have seen.... John 6: 36-37” And Section IV (“And let my cry come unto thee...”) begins with this quote (p. 282): “‘He who abides in love, abides in God, and God in him....’ Saint Paul”

There are a few other tidbits, too, but those should suffice for now.

I also wrote some notes on the sequels, but I’ll save those for another post.

Finally, in the years after I wrote those comments, I went on to write a few blog posts about the Exorcist movies that touched on other aspects of the franchise:

In May 2005, noting that Dominion: Prequel to The Exorcist was coming out on the same weekend as Star Wars: Episode III: Revenge of the Sith, and that both films were prequels to popular 1970s films that affirmed some sort of spirituality in the face of modernity, I compared and contrasted the two franchises.

In December 2013, I noted that the first two Exorcist movies had something else in common with the Star Wars franchise: they both featured an actor who played older than his actual age when we first saw him, and who then played his actual age in prequels or sequel-flashbacks that came out after his first film.

During a ‘Close-Up Blog-a-thon’ in October 2007, I was intrigued by another blogger’s suggestion that some of the subliminal demon-face shots in The Exorcist might have been inspired by Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966).

And in December 2006, I got a kick out of the fact that director William Friedkin, in his director’s commentary to the 1998 DVD edition of The Exorcist, talked about how he avoided the temptation to “pump up” some of the spooky scenes… and then he went ahead and pumped them up anyway in the 2000 re-release!

That last blog post featured before-and-after screencaps from the two versions of The Exorcist, but the layout in the original blog post is somewhat awkward now after all the redesigns that that blog has endured… so I’m going to take advantage of Substack’s “add gallery” feature and re-post that particular item below, too:

The Exorcist — did it need to be “pumped up”?

December 28, 2006

I’m a big fan of The Exorcist (1973), but until recently I had avoided getting the film on DVD — mainly because, by the time I got my first player, there were already two different versions of the film out there, with two completely different sets of extras. I figured I might as well wait until they were packaged together.

My wish finally came true a couple months ago, when Warner put out ‘The Complete Anthology’, including not only both versions of the original film, but both of the sequels and both of the prequels as well — none of which, incidentally, can agree on what happened to the characters before or after the first movie. (One sequel even has flashback scenes that disagree with both of the prequels!)

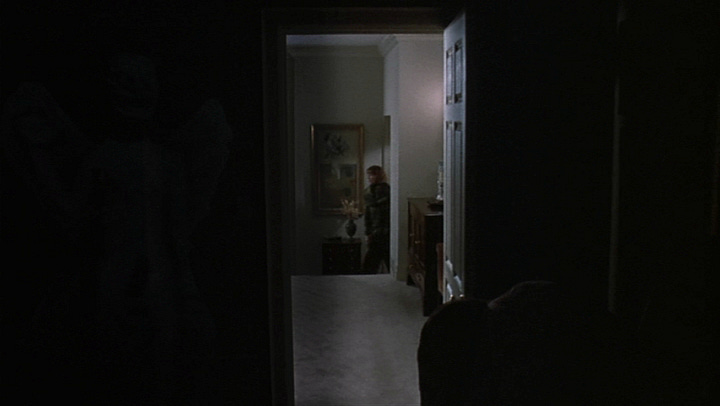

I started listening to the audio commentaries today, and I nearly laughed out loud when I got to the part in director William Friedkin’s commentary, on the “25th Anniversary Edition” that came out in 1998, where he explains what he avoided doing, in the sequence where Ellen Burstyn comes home to find the lights flickering and her daughter’s bedroom window open:

This area here of course has no subliminal imagery. You could have– I mean, the temptation here is to hide little demons in the darkness here. And probably, if they were making the film today, that’s what they would do, is to pump it up. But I tried to hold onto realism as long as I could.

Why did I almost laugh? Because I could vividly remember how “The Version You’ve Never Seen”, an extended version released to theatres only two years after this DVD came out, did hide little demons in the darkness! Here are the relevant shots, with the 1973 version on the left and the 2000 version on the right:

I always thought those additions were pretty unnecessary, and it’s funny to hear Friedkin say so himself — two years before he added them anyway! I wonder what made him change his mind. I haven’t listened to the full commentary on the 2000 version yet, but on this particular scene, he doesn’t address the additions at all.

Incidentally—this is the 2023 me speaking again—Friedkin’s revisions to The Exorcist are all the more interesting to think about now in light of the recent controversy over the censorship of Friedkin’s 1971 Best Picture winner The French Connection.

The censorship, which involved a racist slur used by a racist character, was first noticed when the film became available on the Criterion Channel in June. Disney, the studio that currently owns the film, claimed that the censored version of the film was a “Director’s Edit”, which seemed to imply that Friedkin himself had authorized the change to the film. (Curiously, in countries like Canada where the film could be streamed on Disney+, it was the uncensored version of the film that was streaming.)

Friedkin himself, alas, died in August without confirming whether he had approved of the censorship, so we might never know if he really did. But if he did, then—between The French Connection and The Exorcist—we have at least two cases where Friedkin spent years defending his approach to certain scenes in his best-known films, only to change those scenes anyway decades after the films first came out.

Anyhoo. That about sums up what I’ve written about the original Exorcist. Coming soon: my notes (no formal reviews, alas) on the first two sequels.