Flashback: Close-ups on non-human faces in Ridley Scott's Alien

The recurring motif ties into the film's blurring of the lines between human, animal, and machine.

A new Alien movie came out this week, so I figured I’d link to a few things I’ve written about the earlier films in the franchise, including my review of Alien vs Predator for Christianity Today Movies in 2004 and an article I wrote on Alien and Prometheus for Books & Culture in 2012. I also wanted to link to a blog post that I wrote in 2012 after re-watching the original Alien—but the site I was writing for at the time has gone through a few redesigns, and the post itself, which was very image-heavy to begin with, is now cluttered with ads. So I’m posting an ad-free version of that post here, with a few minor tweaks for style and/or clarity.

Beings, beasts and machines ready for their close-ups

FilmChat | July 3, 2012

Like a lot of people, I made a point of re-watching Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) before Prometheus came out last month. One thing that struck me on this viewing was how frequently Scott uses close-ups of non-human faces, indeed of mere things. I had certainly noticed individual shots on previous viewings, but it was only during my latest encounter with the film that all these images began to jostle together in my mind, and that I began to realize how Scott was using them to further one of the film’s key elements, which is the recurrent blurring of the lines between human, animal and machine.

Consider these images, captured from the film:

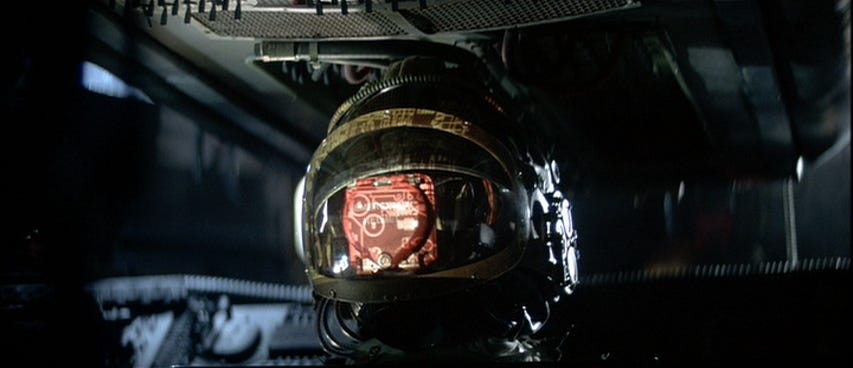

First, the two helmets that happen to be sitting opposite the two computers that talk to each other at the beginning of the film, while all of the human characters are still in suspended animation; note how the computers’ screens are reflected in the helmets’ visors, which lends a sort of “face” to the computers’ communication:

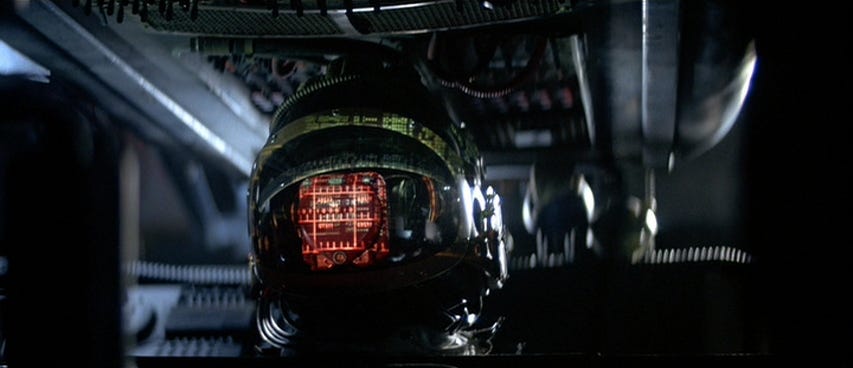

Second, there is our final glimpse of the “space jockey”, as Dallas begins to walk away from the fossilized corpse and the camera zooms in past his helmet to dwell on what looks like an alien skull, lost in shadow:

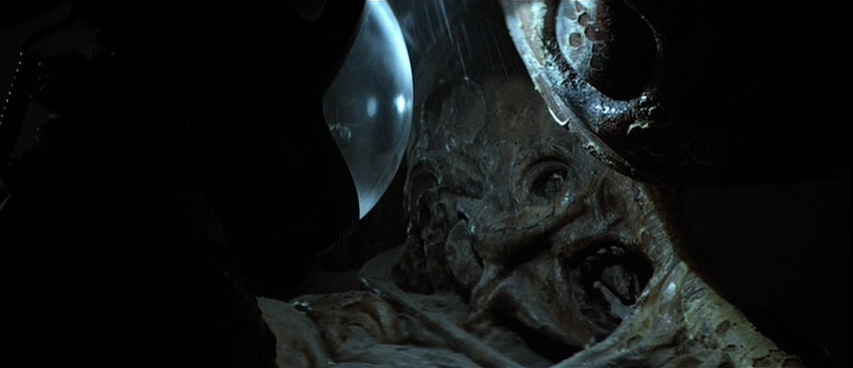

Third, there is the look on the cat’s face as it watches the adult alien kill the first of its victims; the human can be heard screaming off-screen, but the cat’s face remains passive, more or less:

Fourth, there is the head of Ash, the android, after it has been knocked clear off his shoulders; there are two shots from this angle, one of which takes place after the rest of the body has begun lunging at the humans again (so there is an interesting contrast between the lifelessness of the face and the animation, as it were, of the body):

Fifth, there is our last look at Ash a scene or two later, as the flames burn off his skin to reveal the mannequin-like face mold beneath:

And sixth, there is, of course the Xenomorph itself, the face of which is virtually featureless save for its two-stage mouth; there are many shots I could have picked for this creature, but I like this one because it shows the alien contemplating the cat:

And after all we’ve seen in these other close-ups, how does the movie end? With a close-up of Ripley’s face in suspended animation:

I don’t want to say too much about where I think this might be going, partly because I’m still mulling it over myself. But I think it’s instructive that screenwriter Dan O’Bannon said he changed the screenplay’s title from “Star Beast” to “Alien” partly because the word “alien” works as both a noun and an adjective. It’s a word that can be applied to something other than extra-terrestrials; it’s a word that can be applied to those things around us that are animal or machine, and are thus different from us, but it can also be applied to those parts of us that feel strange and “other” precisely because they are not animal or machine, or maybe even because they are.

I think it’s especially interesting, then, that the “space jockey” shot above is a zoom shot, and not a static shot like most of the others. It is almost as though Ridley Scott was trying to draw our attention to the “space jockey” in a way that suggests there is something extra important here — something that might give us a key to understanding what the movie is all about.

And if part of the point of the film is the blurring of lines between being, beast and machine, then the “space jockey”, as conceptualized here, is of course the most blurred entity in the entire film. As the pilot, apparently, of a doomed spaceship, it was presumably an intelligent being of some sort; but its appearance is like that of a beast, rather than anything we might recognize as human; and its body seems to grow out of the spaceship, so that it is not clear where organism ends and mechanism begins.

Alas, as those who have seen Prometheus know, Ridley Scott pretty much abandons everything the “space jockey” stood for in his prequel. In the new continuity, the “space jockeys” are actually just tall humanoids wearing a very peculiar kind of spacesuit, and it is fairly easy to separate the suits from the beings who wear them.

I’ll have more to say about that later. But in the meantime, are there any significant close-ups in Prometheus? Not really. There are one or two wide shots of giant face-statues, such as the one that appears at the top of this post, that look like close-ups (which reminds me of an old Jim Emerson post on Hitchcock’s use of Mount Rushmore in North by Northwest, incidentally). But apart from a rather silly scene in which a few people try to re-animate a 2,000-year-old decapitated head, nothing comes to mind.

There endeth the blog post. I also made some of those points in the Prometheus review that I wrote for Books & Culture. These are the two relevant paragraphs:

In the Soup / Ridley Scott’s “Prometheus.”

Books & Culture | September/October 2012

. . . One of the more striking techniques Ridley Scott used to blur these lines [between human, animal, and machine in Alien] was his repeated close-ups of non-humans, indeed of mere things. Before any of the human characters have woken from their stasis, the film shows us a conversation between two of the ship’s computers—a conversation that is reflected in the visors of two helmets that happen to be sitting opposite the computer screens. Later, when the adult alien claims its first victim (not counting the poor guy whose body hosted the alien in the first place), Scott cuts to a close-up of the ship’s mascot, a cat, as it watches; the human victim screams, off-screen, in terror and pain, but the cat remains passive. Several scenes later, Ash is revealed to be an android when he gets into a fight with his shipmates and one of them literally knocks his head off his shoulders: the camera lingers on Ash’s dangling head as his body keeps twitching and lunging, and it lingers again when the android’s remains are set on fire and the skin peels back to reveal the blank, mannequin-like face mold beneath. And then, of course, there is the almost featureless face of the xenomorph itself: it has no eyes, nor any visible ears or nose, but it can sense its victims all the same. (In something of a twofer, there is even a brief shot in which the alien observes the cat.) By the time the film concludes with a close-up of Ripley sleeping in suspended animation again, the viewer is left to wonder if there is any more life or soul behind those lidded eyes than there was behind all the other bestial, mechanical faces that the camera lingered on.

And, as it happens, one of the most effective close-ups concerned the “space jockey” it-self—an entity that seemed to almost grow out of its ship, thus blurring the lines between organism and mechanism even more. As the human explorers step away from its remains, the camera zooms in past them to come in tighter on the creature, even though it is mostly hidden in shadow; Scott seems to be telling us that the key to the movie may be lurking somewhere in there. . . .

One last note: Ridley Scott’s penchant for “monumental faces”, like the one from Prometheus at the top of this post, was reflected again just two years later in his Bible movie, 2014’s Exodus: Gods and Kings. This is the very first image that was released for that film, one year before the film itself came out: